Digital Media's Disruption of Journalism

Who Controls the News and Where Do We Go From Here?

The once-stable pillars of subscription fees and advertising revenue that supported newspapers for decades have crumbled in the Internet age. As a result, many news organizations have faced financial collapse, leading to newsroom layoffs, paper closures, and desperate sales to wealthy owners or hedge funds as a last resort. This analysis examines the collapse of traditional media revenue, the trend of billionaires and hedge funds buying up newspapers, the rise of nonprofit and reader-supported news models, and potential paths to sustain a trustworthy press in the digital era.

The digital revolution in the 2000s and 2010s brought free online news and new advertising channels, dramatically eroding newspapers' income. The result led to print advertising plummeting: US newspaper print ad revenue dropped by over 60% in the past decade, a staggering decline that left many publications unable to sustain operations. Classified ads went online: Websites like Craigslist wiped out the lucrative classified ad business – one study found Craigslist cost US newspapers around $5 billion in lost classified revenue from 2000–2007. Audiences moved to the web: Readers increasingly got news from internet portals and later social media feeds, expecting free and on-demand content. Meanwhile, Google and Facebook captured the lion's share of digital advertising, leaving legacy news outlets with a much smaller ad spend.

Faced with these shifts, newspapers struggled to adapt. Some tried paywalls or digital subscriptions, but many were too late or too local to attract sufficient paying subscribers. The outcome was a wave of layoffs, closures, and consolidation across the industry. Over the last 15 years, more than a quarter of American newspapers have collapsed or left the business. Total US newspaper employment has fallen by over 50% since 2000, meaning tens of thousands of journalism jobs have vanished. Even major papers that survived are shells of their former selves – for example, The Los Angeles Times now has about 550 newsroom staff, less than half its peak decades ago. The most dire consequence has been the rise of "news deserts" – hundreds of communities have no local newspaper. This leaves residents reliant on social media or partisan national outlets for information, undermining informed civic engagement. The collapse of the traditional revenue model for news has thus been an economic story and a democratic crisis.

Billionaires and Hedge Fund Takeovers

With many newspapers on the brink, wealthy individuals and investment firms have swooped in to buy them – sometimes as acts of journalistic philanthropy, other times as profit-seeking ventures. Today, billionaires or financial firms own a large share of American newspapers. Roughly half of all US daily newspapers are now owned by investment groups (hedge funds or private equity), and a handful of ultra-wealthy owners control many of the rest. This trend has raised questions about editorial independence, content quality, and political influence in the newsroom.

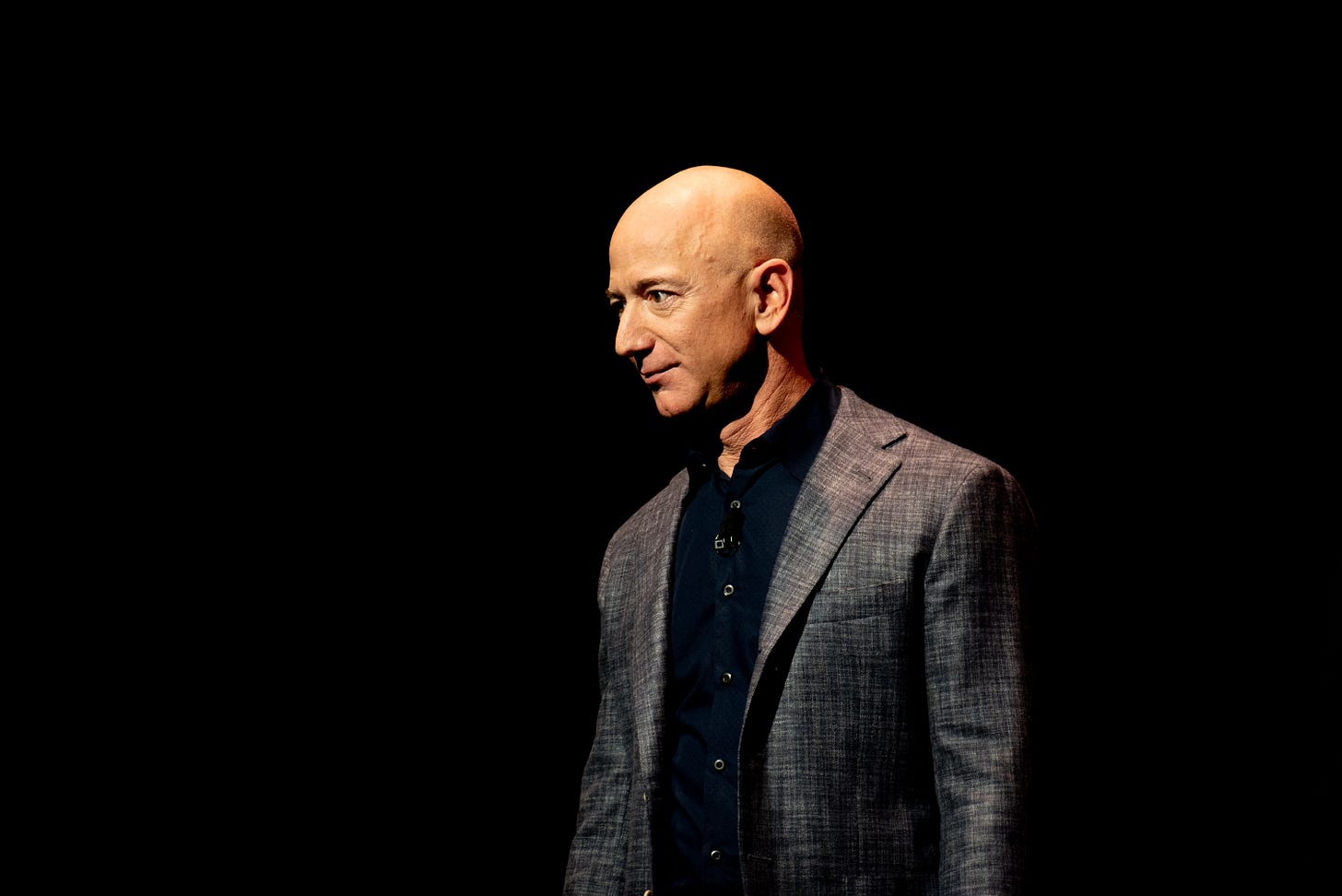

Some billionaire owners have positioned themselves as benefactors of journalism. For instance, in 2013, Amazon founder Jeff Bezos purchased the struggling Washington Post for $250 million, ending generations of Graham family ownership. The Post had been "in a downward spiral" of cuts and declining relevance. Still, Bezos's infusion of money "changed everything," allowing the paper to bulk up its newsroom and reinvent its technology. Under Bezos, the Post rapidly expanded its digital coverage and became a dominant national voice. However, such ownership isn't without concerns. Bezos's vast business empire creates an ever-present conflict of interest – virtually every policy issue the Post might cover (from antitrust to labor to taxes) could affect Bezos's other interests. His ownership raises whether coverage is influenced (or self-censored) to avoid angering the owner. Bezos has primarily kept a hands-off editorial stance. Still, he has made some moves (such as shifting the Post's opinion section toward a free-market emphasis) that suggest his libertarian leanings can trickle into the paper's direction. The Post's turnaround under Bezos demonstrates the positive side of a billionaire owner willing to invest in journalism. Still, it also exemplifies the new reality that a single tycoon's worldview and business entanglements hover in the background of a major news outlet.

In 2018, biotech billionaire Patrick Soon-Shiong bought the LA Times (along with several other California papers) for about $500 million, rescuing it from a Chicago-based chain (Tronc) notorious for cost-cutting. Soon-Shiong presented himself as a civic-minded savior, vowing to rebuild the Times and not interfere in editorial matters. He moved the paper into a new headquarters and hired more staff, even earning the paper multiple Pulitzer Prizes under his ownership. In many ways, this has been an attempt to restore a storied institution to glory. Yet the Times is still finding its footing in the digital era. Despite Soon-Shiong's deep pockets, the paper remains unprofitable, and staff have expressed uncertainty about his long-term vision. Tensions emerged when Soon-Shiong's family members (such as his daughter, who was involved in advocacy) were seen as meddling in coverage and endorsements, raising questions about boundaries. In short, a benevolent billionaire owner can stop the bleeding and invest in quality. Still, there is always a risk of new forms of influence or management turmoil that wouldn't exist under more traditional ownership.

The most ominous trend has been the takeover of newspapers by hedge funds like Alden Global Capital, which operates with a pure profit motive. Alden has become the second-largest newspaper owner in the US (owning hundreds of titles, including the Chicago Tribune, Denver Post, Boston Herald, and many regional papers). Its reputation in the industry is grim. Media observers have dubbed Alden "one of the most ruthless…strip-miners" of local journalism, and Vanity Fair nicknamed it the "grim reaper" of American newspapers. The reason? Alden's business model is brutally simple: buy newspapers, then "gut the staff, sell the real estate, jack up subscription prices, and wring as much cash as possible" out of them. Public service or editorial quality is barely a consideration. Researchers found that Alden-owned papers cut their newsroom staff at twice the rate of other newspapers, leading to ghost papers that contain little original reporting.

In many cases, Alden papers rely on wire services or syndicated content to fill pages after firing local journalists. Notably, Alden has also been willing to use its papers for political or lobbying ends – for example, orchestrating editorials across dozens of papers attacking legislation Big Tech opposed. The Alden approach highlights the worst-case scenario of the new ownership landscape: profit-driven owners who extract value from news outlets without regard for their community role. Under such owners, editorial independence can be compromised not by direct ideological meddling but by the absence of resources to do hard-hitting journalism (or by subtle pressure to avoid angering advertisers and business partners).

Billionaire and hedge-fund takeovers have been a double-edged sword. On one hand, they've kept some newspapers that might otherwise have died. On the other, they concentrate media power in fewer hands and often impose profit-first strategies on an industry with a civic mission. When a billionaire owns a newspaper, its survival may be less risky, but there is an implicit dependence on the owner's goodwill and lack of interference. And when a hedge fund like Alden owns a paper, survival often comes at the cost of severely diminished journalism. This new era raises urgent questions: Does the news serve the public or proprietor's interest? And if quality journalism isn't profitable, who will fund it – benevolent billionaires or nobody?

The Shift to Nonprofit and Reader-Supported Models

As traditional for-profit models falter, an alternative path has gained momentum: news organizations restructuring as nonprofits or relying directly on their readers for support. These models aim to prioritize journalism over profits, treating news as a public good rather than a commodity. Several high-profile outlets have succeeded with this approach, suggesting it could be a blueprint for the future.

The Guardian (UK) has pioneered a unique funding model among significant newspapers. It is owned by the Scott Trust (a nonprofit trust) rather than shareholders, which means it has no pressure to deliver profits – any surplus is reinvested into journalism. In the mid-2010s, The Guardian boldly moved to remove its paywall and make all content free, instead asking readers for voluntary contributions. The result has been surprisingly positive. After losing £85 million in 2015, The Guardian implemented a reader contribution strategy that transformed its finances from heavy losses to profitability. By 2022, over 1 million readers worldwide had become paying supporters (through small donations, memberships, or subscriptions), providing a sustainable revenue stream. The paper’s community-funded approach proved that a major news outlet can thrive without charging for content – as long as enough readers believe in its mission. The Guardian's global readership now chips in from around the world, and the paper has continued to provide robust reporting (including award-winning investigative and climate journalism) supported by these reader donations. The key has been building trust and loyalty: The Guardian emphasizes its independence and public-service mission in appeals to readers. While it still earns money from advertising and other sources, the shift to a nonprofit-style ethos – "owned by readers" in spirit – has enabled The Guardian to remain free and financially stable. This model prioritizes impact over profit, aligning the business and journalistic sides.

Founded in 2007, ProPublica is a trailblazing example of nonprofit, donor-funded journalism in the United States. It was established explicitly as an independent investigative newsroom, supported by philanthropic grants and donations rather than ads or subscription fees. ProPublica's work is offered free online and often published in partnership with mainstream outlets to reach a broad audience. Their revolutionary model has yielded remarkable results: in 2010, ProPublica became the first digital-only news organization to win a Pulitzer Prize for its investigative reporting, and it has since won six Pulitzers in total across various categories – a testament to the quality and impact of its journalism. With a team of over 150 journalists, ProPublica produces in-depth investigations that many profit-driven newsrooms can no longer afford to do. Its stories – from uncovering hospital abuses after Hurricane Katrina to revealing financial conflicts among Supreme Court justices – have spurred reforms and earned national acclaim. ProPublica's funding comes from charitable foundations and thousands of small donors, including the Sandler Foundation, Knight Foundation, and many others. This broad support base insulates it from any single benefactor's pressures. By "using a donor-based model that allows them to keep their website open to everyone," ProPublica has essentially reinvented the business model of investigative news. Its success demonstrates that nonprofit journalism can step in to do the hard work that market-driven outlets are increasingly abandoning.

Beyond these prominent examples, a growing ecosystem of nonprofit and reader-supported news organizations has emerged. Investigative studios like The Center for Investigative Reporting and The Marshall Project rely on donations to produce specialized journalism. Many local news sites and digital publications have launched as 501(c)(3) nonprofits or converted to that status through the IRS. In 2019, The Salt Lake Tribune became the first legacy US daily newspaper to obtain nonprofit status as a charity, potentially blazing a trail for others to follow. Its move acknowledged that the paper's public-service value to the community outweighed any profit motive. Similarly, a nonprofit institute now owns the Philadelphia Inquirer thanks to a wealthy donor's endowment, ensuring any profits return to the newsroom. Some digital media startups have even adopted membership models or cooperative structures (for example, The Texas Tribune uses a mix of donations, sponsorships, and events to fund its statewide reporting and has thrived as a nonprofit newsroom).

Meanwhile, NPR and PBS – though not fully nonprofit-owned (they receive some government funding) – operate on a member-support model where listeners and viewers donate to sustain the service. All these efforts share a philosophy: quality journalism may need to be treated as a mission-driven public service, not a high-margin business. By shedding the expectations of high profitability, nonprofit news organizations can focus on their journalistic mandate and measure success in terms of impact rather than earnings.

This shift toward nonprofit and reader-funded media suggests a possible way forward for the news industry. Instead of chasing clicks or catering to owners' whims, these organizations are directly accountable to the readers, listeners, or donors who value their work. They are more transparent about their funding and often publish annual reports to show how funds are used for reporting. Of course, the nonprofit model isn't a panacea – fundraising is a constant concern, and not every community can quickly drum up philanthropic support. However, as traditional commercial media continues to struggle, we can expect more newsrooms to explore conversions to nonprofit status or hybrid models (for-profit companies with nonprofit arms for investigative work) to sustain themselves. The success of entities like The Guardian and ProPublica in maintaining editorial quality and growth without traditional profits provides a hopeful example that journalism can survive and even thrive with public support.

Where Do We Go From Here?

If the past two decades have taught us anything, the future of trustworthy news will depend on new forms of support and engagement between the press and the public. Digital media's disruption has broken the old model and opened up opportunities for consumers, journalists, and policymakers to reshape the media landscape.

Ultimately, if we value independent journalism, we may need to pay for it directly. Media consumers can play a crucial role by financially supporting reputable news sources through digital subscriptions, paid memberships, or one-time contributions. Subscribing to your local newspaper or a quality national outlet provides them with resources to report the news. For outlets that don't have paywalls, consider donating if you read them regularly (for example, The Guardian's millions of free readers sustaining it via voluntary donations). Supporting nonprofit investigative groups – say, contributing to ProPublica or local investigative funds – also fuels deep reporting that benefits the public.

Even micro-payments or crowdfunding can help; in recent years, journalists have launched Kickstarter campaigns for specific projects, and platforms like Patreon allow individuals to fund journalists or podcasters directly. Each person's contribution might seem small, but collectively, this revenue can make a newsroom viable. The key is a shift in mindset: instead of assuming news will be free, we recognize it as a service worth paying for, much like we pay for streaming entertainment or music. Unlike click-driven revenue, reader revenue incentivizes outlets to serve their subscribers with quality and trustworthiness. It creates direct accountability: subscribers can cancel if a publication betrays trust – a feedback loop that rewards credibility. By voting with their wallets for the kind of journalism they want, consumers can encourage media organizations to prioritize accuracy and depth over sensationalism.

Another avenue is growth in philanthropic funding for journalism. Foundations, charities, and yes, even public-spirited billionaires can invest in news as a social good. We already see this with initiatives like the American Journalism Project and local community foundations stepping in to fund reporting on under-covered issues. Wealthy individuals who buy newspapers can run them more like a public trust than a business – for example, by endowing them or converting them to nonprofit status (as Gerry Lenfest did with the Philadelphia Inquirer). More news organizations may need to follow the nonprofit or hybrid model to ensure long-term survival. This could include newspapers partnering with universities or nonprofits or establishing endowments whose interest funds reporting costs. Importantly, philanthropy in journalism should be structured to preserve editorial independence (no-strings-attached funding). One promising development is the rise of consortiums that pool funds for local journalism so that no single donor has outsized influence. If the ethos of public broadcasting can be extended – where communities collectively donate to keep the news flowing – it might counterbalance the loss of commercial revenues.

A more systemic solution often raised by media experts is considering a publicly funded news model on a scale the US has never seen. Countries like the UK, Canada, and those in Scandinavia invest heavily in public broadcasters (such as the BBC or CBC), which provide high-quality news as a public service. These nations spend roughly $100 per citizen annually on public media, whereas the United States spends only about $1.40 per capita (approximately $465 million in total federal funding in 2020). The US ranks near the bottom among democracies in government media funding, at just 0.002% of GDP. American public broadcasters NPR and PBS manage to produce generally trusted news and cultural programming. Still, they do so on shoestring budgets – they rely primarily on private donations and grants because government support is so meager.

Boosting public funding for media could significantly strengthen journalism, especially in areas the market ignores (like rural news, educational programming, or emergency local reporting). Research indicates that countries with robustly funded public media have more informed citizens and higher levels of civic engagement. A more extensive, well-funded public media system in the US – an "American BBC" – could provide a baseline of factual news accessible to all, helping combat misinformation and polarization. For example, this might be expanding PBS/NPR with multiple channels or digital platforms or creating grants for investigative journalism akin to how the National Science Foundation supports science. Of course, implementing this faces challenges.

The idea of government-funded media raises skepticism in America; there is a longstanding resistance to public subsidies for journalism, rooted in fears of state influence or simply a belief that the press should be a private enterprise. Any publicly funded model would need strong firewalls to ensure editorial independence (to prevent political meddling) and bipartisan buy-in that a well-informed populace is a common good. Expanding public media funding would require overcoming partisan distrust in the current polarized climate – but it's not impossible. Notably, public media like NPR/PBS consistently rank among the most trusted news sources in the US, suggesting that they could help restore faith in media generally if scaled up. A mixed model may emerge: government funding to support local journalism initiatives and public-interest reporting, combined with community oversight to keep them fair and balanced.

Finally, the future of trustworthy news also depends on citizens becoming savvy news consumers and advocates. This means educating the public about how quality journalism is produced and why it matters. If consumers demand better news and support it, the market (and policymakers) will respond. People can foster a culture that values truth by actively sharing credible news, calling out misinformation, and supporting journalism initiatives in their communities (for example, attending local journalism events or school news literacy programs). In addition, voters can push for policies that bolster journalism – such as tax incentives for subscribing to local papers or laws that make Big Tech pay their fair share to news producers when news content drives engagement on those platforms. Even something as simple as writing a letter to a local editor or volunteering as a community contributor can strengthen the connection between newsrooms and the public they serve.

In navigating these solutions, it's clear there is no one magic fix. The economic forces that disrupted journalism are complex and still evolving. However, the overarching theme is a re-alignment of journalism with the public interest. Whether through nonprofit ownership, reader funding, or public funding, the goal is to reduce journalism's dependency on clicks, ads, and billionaire patrons and increase its accountability to the communities it informs.

One encouraging sign is that despite all the turmoil, new models of journalism are sprouting, and some are thriving. Nonprofit outlets are winning Pulitzer Prizes. Local newsletters and niche sites are building loyal audiences willing to pay a few dollars a month. Collaborations between big and small newsrooms (often grant-funded) are tackling big investigative projects. And even the legacy media, now mostly under new ownership, have realized that their long-term survival hinges on trust – a commodity that must be earned, not bought.

As consumers of news, we all have a stake in this. The information ecosystem we end up with reflects what we choose to read, share, and support. By seeking out reputable sources and being willing to contribute to them, audiences can help good journalism find a sustainable path. Conversely, journalists and media organizations must continue experimenting with business models that put quality first, even if that means being smaller or structured differently than in the past. It may also require embracing a degree of transparency and community involvement that traditional media was not accustomed to.

The digital age has undeniably upended the old order of journalism – shattering profits, changing ownership, and flooding the world with content – but it has also prompted a necessary reckoning and rebirth. The collapse of the advertising-driven model has hurt journalism, yet it has also forced the industry to innovate and refocus on its core mission. By learning from the failures and successes so far, we can move toward a media landscape where news is abundant but accurate, journalists can do their jobs without fearing financial ruin, and when the public actively participates in sustaining the flow of reliable information. The stakes for democracy are high: a free society depends on a free press, and in the digital era, "free" may no longer mean without cost but relatively free of the constraints that made news a mere commodity. The hope is that journalism's next chapter – written with the support of readers, donors, and maybe a touch of enlightened policy – will be one in which trust and truth find a new equilibrium.